Cynthia Lim has been researching her family’s immigration path to the United States after a visit to China to find her ancestral villages with the “Roots Plus” program. She is working on a memoir to document her journey. She is the author of Wherever You Are: A Memoir of Love, Marriage and Brain Injury and her essays have appeared in various literary journals. She retired as a central office administrator with the Los Angeles Unified School District and holds a PhD in Social Welfare. Find out more about Cynthia at cynthialimwriting.com .

My Father Was My Gateway To American Life. Then I Found Out He Lied To Get Into This Country.

Originally published in the Huffington Post, May 28, 2022

“Reading their files made me uneasy. Their claim to citizenship was based on a lie. Were they ‘illegal immigrants’? Did that mean I wasn’t a true American?”

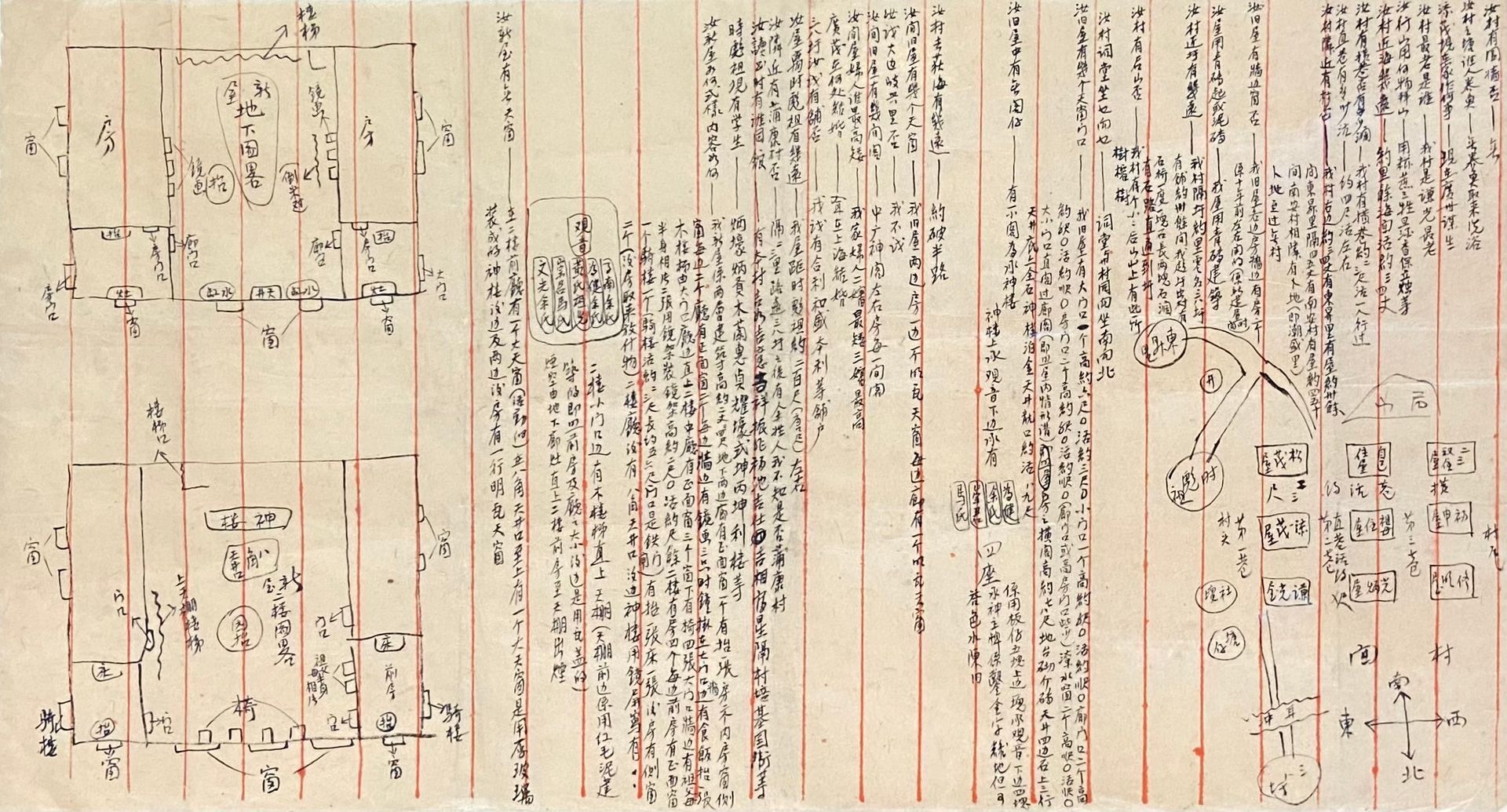

Mow Lim, in Tulare, California, in 1946.

COURTESY OF CYNTHIA LIM

The one thing I thought I knew for certain was that my Chinese father, Mow Lim, was allowed to immigrate in the 1940s because my grandfather was a U.S. citizen. I never questioned that fact or found out how Grandfather Sam, himself an immigrant, earned his citizenship. Nor could I ask my father these questions. He was killed in a plane crash in 1964, when I was 7.

I adored my father and loved the stories my mother told me. He arrived on a steamship alone when he was 12, then moved from San Francisco to Tulare in the Central Valley in his teens. Butchering in a meat market during the day, he rode a bicycle to night school to learn English. He adopted the American name “Don” and, at 19, served in the U.S. Army in World War II. On a visit to China, he was matched to my mother. After they married, they had five children and he entered the grocery business. Before his death at 36, he owned a store in Castroville, California, and had a share of a larger one in Salinas.

His photos in our albums comforted me for years after his death. He looked handsome and debonair with his arched eyebrows and easy smile. My eyes were always drawn to the picture of him in his teens, with a white T-shirt and rolled-up chinos.

He had been my gateway to American life. He bought my sister a portable record player and dozens of 45s, and we listened to Barbara Lewis’ “Hello Stranger” and Lesley Gore’s “It’s My Party” long after his death. He enrolled us in music and dance lessons. On his rare days off, he took us to the Santa Cruz boardwalk or to Pacific Grove to collect shells. As the baby in the family, I got to sit on his lap in the evening and I would try to synchronize my breathing with his.

After his death, my widowed mother was left with five children, aged 7 to 15, two grocery businesses and limited English. Cantonese became the primary language at home and Chinese instrumental music replaced the soundtrack to “Oklahoma” on the stereo. I wasn’t interested in my native culture. I wanted meatloaf with mashed potatoes or Taco Bell instead of the ground pork with salted fish and spare ribs with black bean sauce my grandmother made. I longed to go to summer camp and learn to canoe or vacation in Cape Cod and eat blueberries straight off the vines like the girls I read about in the books at the public library. Instead, my childhood and adolescence were spent working at the grocery store.

“Are you going to marry Chinese?” my grandmother used to ask me. I always said yes because I wanted a partner who saw the importance of family, of saving face and being modest. In college, I met my Jewish boyfriend who embodied those traits and valued me. We married and settled in Los Angeles, where I pursued a career in social work and education. We raised two sons who were proud of their mixed heritage. I was confident of my citizenship and place in this country.

It wasn’t until 2017 that I researched our history and realized how little I knew about my father’s life before he came to America. He’d left China during the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned the entry of laborers from 1882 to 1943. It was the only piece of legislation that barred a specific ethnic group from entering this nation and from becoming naturalized citizens. There was an exemption for sons of native-born U.S. citizens. Was that how my father was able to come?

Some Chinese evaded the ban by claiming to be sons of native-born citizens. Men would testify that they were born in the U.S. and then provide witnesses affirming that fact. Once declared citizens by the government, they’d visit China, then report the birth of sons when they came back. Those offspring were eligible to immigrate due to birthright citizenship. Thousands of Chinese entered the U.S. during the exclusion act using false papers. They were called “paper sons.”

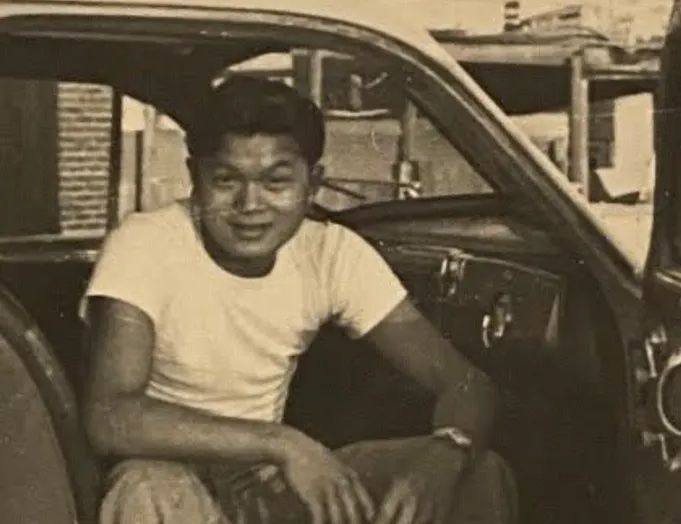

Mow Lim, in San Francisco, California, 1941.

COURTESY OF CYNTHIA LIM

In 1906, all birth records in San Francisco burned in fires after the earthquake, leading to a flood of false papers. Chinese already in the U.S. declared under oath that they were born here and had sons in China. We knew of families with “paper” names and real clan names and brothers with different last names because of assumed identities. But I didn’t think that was the case with my father or grandfather.

What I found at the National Archives in San Bruno proved otherwise. My father’s case file contained transcripts and photos that documented his arrival. He was detained for 43 days before being interviewed by three inspectors. Barely 14 at the time, with cheeks still chubby with baby fat, they asked him 155 questions about his kinship and village life, trying to catch him in a lie.

“Were your paternal grandmother’s feet ever bound?”

“Has your village a fish pond?”

“Were the tables and chairs the property of the school or individuals?”

The interrogation took two days, each question and answer translated through an interpreter. There were some lies in his testimony. He said that his grandfather, my great-grandfather, was born in the United States, but I knew that wasn’t true. The grandfather was really his great-uncle Ock Jit, born in the Guangdong province, according to relatives.

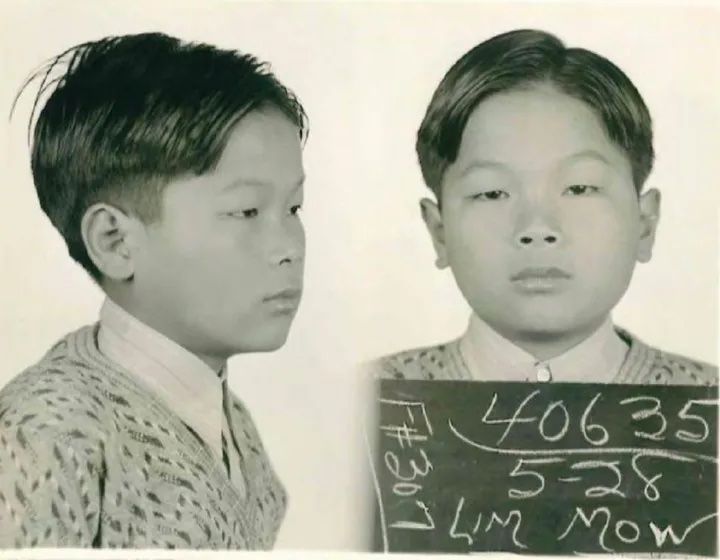

I requested files for Grandfather Sam, as well as Ock Jit, from the National Archives, where I discovered our clan’s path to the United States. In 1894, Ock Jit arrived in San Francisco via steamship. Wearing a black skull cap and black shirt, he told authorities he’d been born in Chinatown but went back to Guangdong for a visit and was now re-entering.

He was detained but filed a writ of habeas corpus with the federal courts. His testimony, and that of two witnesses, convinced the judge he was from San Francisco and he was declared a native-born citizen. In subsequent visits to China, he returned to San Francisco and declared the birth of sons (one was my grandfather though he was really a nephew). Ock Jit had one son but said he had four. In total, seven men were let into America as his sons and grandsons.

The author’s great-great-uncle, Ock Jit, in 1894.

COURTESY OF CYNTHIA LIM

Reading their files made me uneasy. Their claim to citizenship was based on a lie. Were they “illegal immigrants”? Did that mean I wasn’t a true American? After the 2016 presidential election, the new administration railed against foreigners, documented and undocumented. There was talk of a Muslim ban. Would Chinese be singled out again? Would our status as citizens undergo scrutiny after the fact?

But as I studied the story Ock Jit’s descendants told when they arrived, I couldn’t fault them for lying. Like all immigrants, they were seeking a better life for themselves and future generations. I was impressed by how they educated themselves on the exemptions in the exclusion act and used the government’s legal processes in their favor. They retained white attorneys knowledgeable of the judicial system to file the necessary paperwork for hearings. They took their cases to federal courts.

I wondered if my father had any qualms about the deception. For many that entered during the exclusion era, there were fears of deportation if real relationships or names were revealed. My brother remembered my parents hiding the Chinese writing on a framed picture in case there was a surprise inspection from immigration.

Fears of intimidation lurked in my mind with the rise of anti-Asian sentiment during the onset of COVID. Nearly a third of Asian-Americans in the San Gabriel Valley experienced hate during the pandemic, according to the LA Times. I thought back to what my ancestors did in the face of harsher times when they were clearly not welcomed here. I felt renewed gratitude for their efforts and reminded myself that this was my home. This was where I was born. And I am a true American.